Lead Exposure During Childhood Is Linked To Brain Deficits In Middle-Age, According To Study

|

| 564 had been tested for levels of lead in their blood when they were 11 years old |

A new study in the Journal of the American Medical Association has revealed a worrying correlation between exposure to high levels of lead during childhood and negative changes to brain structure later in life. According to the study authors, it’s too early to tell if this could contribute to dementia in old age, although there is certainly cause to believe that this may be the case.

The findings are based on a decades-long research project involving 1,037 people who were born in the town of Dunedin, New Zealand, in 1972 and 1973. Because restrictions on leaded gasoline had not yet been implemented at this time, millions of people worldwide were exposed to much higher levels of the heavy metal than is the case today.

Just under 1,000 of the original participants were still alive at the age of 45. Of those, 564 had been tested for levels of lead in their blood when they were 11 years old, which allowed the study authors to examine how this correlated with their brain structure in middle-age.

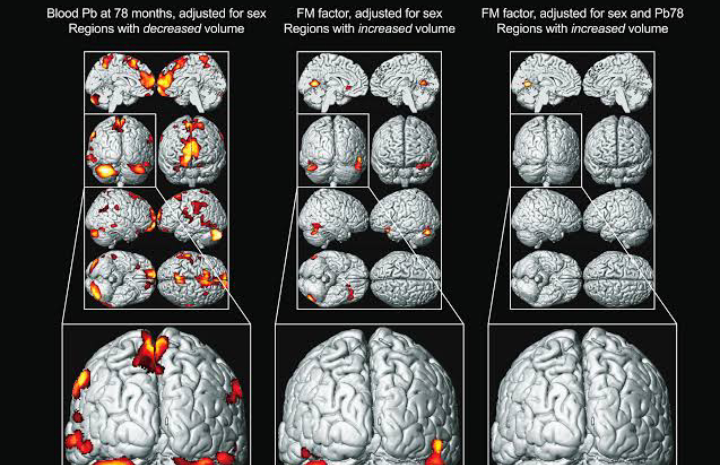

Using magnetic resonance imaging (MRI), the researchers noted a number of adverse changes to the white matter of those who had been exposed to elevated levels of lead as youngsters, with a clear correlation between blood lead concentration at age 11 and the severity of these brain changes.

Specifically, they found that every additional five micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood resulted in a loss of 1.19 centimeters squared of cortical surface area. This same increment in lead concentration was also associated with a decrease of 0.1 cubic centimeters of hippocampal volume.

Because the hippocampus is central to learning and memory, the study authors suggest that this loss of volume may result in an increased vulnerability to dementia later in life. Though they can’t yet confirm this hypothesis, their experiments did reveal that every five micrograms of lead per deciliter of blood at age 11 produced a drop of 2.07 IQ points at age 45.

Commenting on these findings, study author Aaron Reuben explained that “there are deficits and differences in the overall structure of the brain that are apparent decades after exposure.”

“That's important because it helps us understand that people don't seem to recover fully from childhood lead exposure and may, in fact, experience greater problems over time.”

Worryingly, none of the study participants claimed to be suffering from any form of cognitive decline, despite the fact that their friends and relatives tended to disagree, saying that they displayed memory and attention deficits.

Based on these results, the study authors conclude that “adults who were exposed to elevated lead levels as children, including the millions exposed during the peak era of leaded gasoline, could be viewed as potentially at risk of neurodegenerative diseases.”